Contemporary Hum: An interview with the curators of Paradise Camp

June 30, 2022

Arts Monthly Australasia: Paradise Camp

June 30, 2022Metro: Reclaiming Paradise

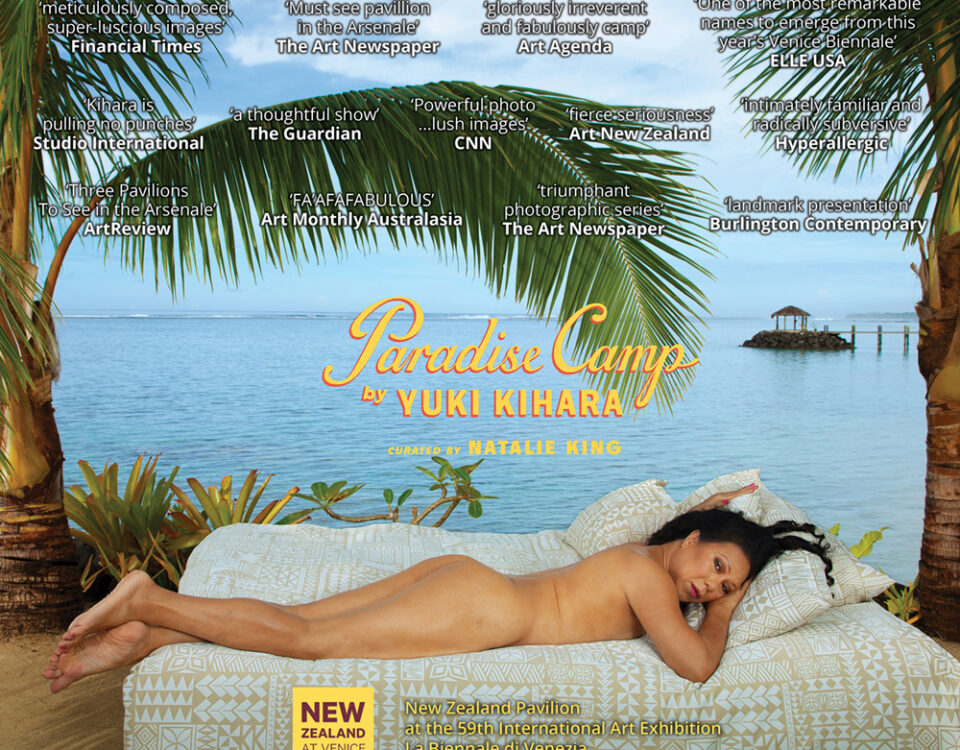

Two Faʻafafine (After Gauguin) [2020] (detail) from Paradise Camp [2020] series by Yuki Kihara. Image courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand

When Australian curator Natalie King first approached Yuki Kihara to propose a project for the New Zealand pavilion at the 2022 Biennale di Venezia (Venice Biennale), Kihara declined.

The biennale is the world’s premier art exhibition. Founded in 1895, it draws more than 600,000 visitors from all around the globe to the sinking city to see the cream of the art world’s crop. But after two previous knock-backs, Kihara felt that “maybe Venice Biennale is not supposed to be for somebody like me”, she tells me. I’m startled by the vulnerability Kihara is expressing and her resignation that this prestigious international art event might not be for her, though she is an artist known for ferocity, determination and ambition. It’s the last part of her sentence that stings — like me.

Of Sāmoan and Japanese heritage, Kihara is an interdisciplinary artist who boasts a long list of previous exhibitions in some of the world’s most significant galleries and museums. In 2020 she was named one of the Arts Foundation Laureates, winning the My Art Visual Arts Award. It would seem that someone like Kihara is on the perfect career trajectory to go to Venice, a sentiment shared by the pleased community rumblings when her unanimous selection was announced in 2019. “Timing is very important with Venice,” King tells me, and clearly this is Kihara’s time.

For the biennale, Kihara will present Paradise Camp, an exhibition that brings with it a lot of firsts for New Zealand — she will be the first Pacific representative, the first Asian representative, and also the first fa’afafine (Sāmoa’s third gender). Suddenly, we see what the words like me point to. Being the first — and in this case also the only — representative of multiple communities comes with great responsibility and an immense weight. The artist acknowledges this particular tension when she tells me she feels as if she is the tip of a dagger that is being repeatedly used to pierce through a surface to cut new openings. Kihara admits that just being in her position “can help to widen the door for many of us who have been excluded from this very, very privileged world”. But, at the same time, “I know that if I fuck up, they will shut the door on us immediately.”

While many of the details of Paradise Camp are embargoed until it opens in April, we do have one clear signpost of what’s to come. “The hero image, the two fa’afafine, is based on Gauguin’s painting of the two Tahitians [Two Tahitian Women]. I call it upcycling. In the context of sustainability, upcycling means that you take something original to improve it. And that’s what I’m doing.”

Read the interview in full here on Metro’s website.