Quite moments of reflection

September 29, 2017

Biennale Arte 2019: New Zealand’s artist and curators announced

November 2, 2017A lesson in empathy: South Africa at Venice

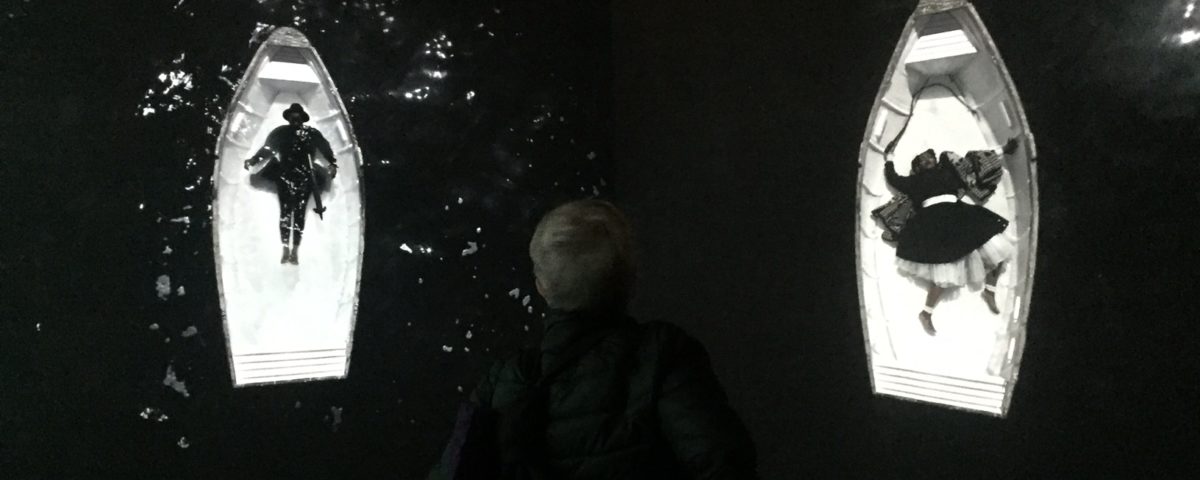

A visitor watches Mohau Modisakeng’s Passage at the South African pavilion. Photo: Julia Craig

Julia Craig, one of our Exhibition Attendants for Lisa Reihana: Emissaries reflects on her encounters with pavilions in the Arsenale in her blog (below).

Visiting Biennale Arte 2017 is an exhausting pursuit. With over 77 artists in the central pavilion and 24 national pavilions at the Arsenale alone – many of these works lengthy video installations – I am not surprised that when people reach the New Zealand pavilion (about 800 metres from the entrance) they complain of art fatigue.

When I first visited the Arsenale I too had the same complaint. However, about half way through, I encountered the South African pavilion and I was reenergised.

South Africa presents two video artists for this year’s Biennale, with a stunning work by Mohau Modisakeng in the first room. There, you are met with three screens. In each screen an individual is shown lying in a boat as a pool of water gradually rises around them. Filmed from a bird’s eye view, each person is framed by the white boat beneath them, and they appear to hover amidst the glistening waters. One character thrashes defiantly, while another floats peacefully, but all three are passengers to the tide.

The stunning imagery, shot in black and white, evokes feelings of struggle and resistance, and reflects the displacement and statelessness of people in South Africa’s colonial history. The imagery echoes the waka in Lisa Reihana’s in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17, at the New Zealand pavilion, as well as its location in the Tese dell’Isolotto, a warehouse in the Arsenale that used to produce ships at a rate of one per day. The boat has powerful symbolism in both works: it is a tool for exploration and the movement of bodies, but also alludes to personal transformation and discovery. This dialogue between personal stories and global movement is explored by the second artist at the South African pavilion.

In the following room you are confronted with a large video projection of Julianne Moore and Alec Baldwin – two instantly recognisable faces that clearly draw a crowd. This is Candice Breitz’s Love Story, in which the two actors are channelling the stories of six individuals who have fled their countries to avoid oppression or persecution. They sit in front of a green screen without the help of any props, costume or setting. This makes you very much aware that these are actors recounting stories that are not their own, and that their privileged lives could not be more distanced from the subject matter. The six refugees Baldwin and Moore depict are: Sarah Ezzat Mardini who escaped war-torn Syria; Mamy Maloba Langa from the Democratic Republic of Congo; Shabeena Francis Saveri, a transgender activist from India; Luis Ernesto Nava Molero, a political dissident from Venezuela; José Maria João, a former child soldier from Angola; and Farah Abdi Mohamed who fled Somalia due to his religious beliefs. Their stories are slickly edited, with shots jumping between Moore and Baldwin and the six different narratives. Common themes of threat, abuse and escape emerge, offering the viewer a generalised narrative of the refugee story.

Alec Baldwin in Candice Breitz’s Love Story. Photo: Julia Craig

In a room behind this are the original video interviews of the six individuals. These are the complete, unscripted and unedited interviews that can last hours long. By this point during my visit to the South African pavilion, I was running out of time and I knew I could only watch some of these video interviews for a few minutes. That is when the power of the artwork struck me: I just gave a lot of my time to two Hollywood actors in an accessible and generalised narrative of the refugee experience, but would I do the same for the real stories in their unedited and idiosyncratic entirety? Do I need stories to be portrayed a certain way in order to empathise with them?

The video interviews with Mamy Maloba Langa and Shabeena Francis Saveri in Candice Breitz’s Love Story.

Breitz expertly made me rethink the narrative forms I give my attention to, and the conditions under which empathy can be fostered. As a society we give so much of our time to celebrity and pop culture, and when we do extend that attention to the refugee crisis and other human stories, do we still expect it to come in a palatable package with some familiar Hollywood faces? “Alec, you’re famous! People will listen to you,” Alec Baldwin says to himself, as he channels José, who aptly conveys the emotional power we bestow on celebrities.

A short walk from the South African pavilion, at the end of the Arsenale complex, is the New Zealand pavilion, Lisa Reihana: Emissaries. Just as demanding for one’s attention at 64 min long (two 32 min long videos with slight variations played back to back) is Reihana’s exhibition centrepiece, in Pursuit of Venus [infected], 2015–17. Probably one of the more lengthy works of the Arsenale, you would be forgiven for thinking that people may not spend an hour with it. But even though the New Zealand pavilion is near the end of the Arsenale (and often near the end of the visitors’ stamina), people seem to be entranced by Reihana’s work, and end up staying for its entirety. Perhaps the work inspires and reenergises them, as the South African pavilion did for me.